Lab animal report for 2023

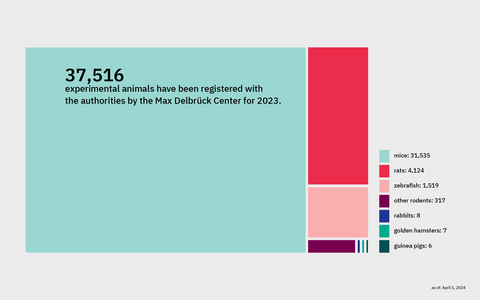

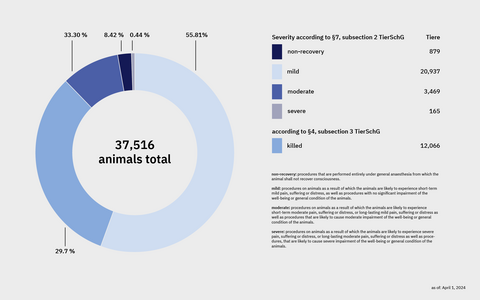

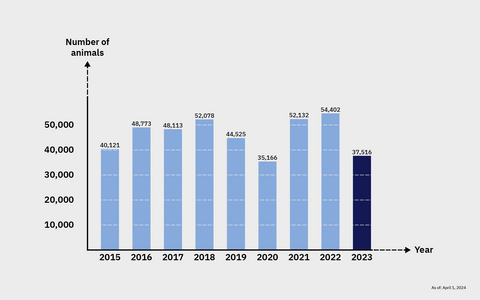

The number of laboratory animals reported by the Max Delbrück Center to the State Office for Health and Social Affairs in Berlin decreased to 37,516 in 2023. That is 16,886 fewer than in 2022. The animals are mostly mice, rats and fish. The number also includes animals used by individual research groups at Charité — Universitätsmedizin, the Leibniz Research Institute for Molecular Pharmacology (FMP), the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH), and the two spin-offs T-knife and Berlin Cures on the campus in Berlin-Buch.

The number of animals used generally fluctuates when projects get underway or are completed, or when a new lab is opened or an existing one is closed. At the same time, the reduction shows that the Center’s consistent implementation of the 3R principles (Reduce, Refine, Replace) is having an effect.

Research teams as well as animal keepers at the Max Delbrück Center receive training regarding lab animal science and 3R methods. The research teams work closely with each other and routinely exchange information to ensure that the number of animals required is kept to a minimum. The Preclinical Research Center on the Buch campus also provides scientists who must perform research on animals with a state-of-the-art facility equipped with tools and technology intended to minimize animal suffering as much as possible. In addition, the Max Delbrück Center is involved in the Berlin-based Einstein Center 3R. Biomedical research institutions in the city have formed a collaborative network to improve unavoidable animal experiments and develop robust alternative methods.

Why do we need animal experiments?

Researchers at the Max Delbrück Center seek to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of health and disease and to understand the basic mechanisms of life. The aim: to find better therapies, to develop new drugs and to reduce patient suffering.

But the human body is a complex system – with interactions between different cell types, organs and organ systems. No experiment in a test tube, however sophisticated, can simulate how cancer cells metastasize on its own, for example, and even the best computer simulations of the effect of a potential therapy must be tested for accuracy on whole organisms. For many questions in the life sciences, there are still no alternatives to animal testing. What methods are necessary and under what circumstances varies depending on the research question being asked.

Further information

- Facts and figures

- Preclinical Research Center

- Einstein Center 3R

- Why we cannot yet avoid animal testing

Contact

Jutta Kramm

Head, Communications

Max Delbrück Center

+49 (0) 30 9406 2140

jutta.kramm@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should be able to benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. This is why the Max Delbrück Center supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly-run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is 90 percent funded by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.