That was the Long Night of Science at MDC

The golden cog is only spotted at second glance. If you want to transport art into space, exhibition space and weight have to be extremely limited. So the bulbous sailing ship, just like 63 other objects, has only one cubic centimeter of space in the Moon Gallery. The compact cube is reminiscent of a letter case and it tells stories. Since February 2022, the collaborative work of art has been floating through space on the International Space Station (ISS), and during the Long Night of the Sciences, a copy of it was on display at the MDC in Berlin Mitte, the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB).

When Irish artist Gillian Fitzpatrick and astrophysicist Dr. Justin Donnelly of Dublin University of Technology envisioned their small sculpture for the cube, the constraints were inspiration: "I immediately thought of solar sails unfolding to their full size in space, where they power space probes. They look golden to us," Donnelly told the visitors. His associations wandered to a love poem John Donne had written for his wife before a trip to Europe. The souls are not separated despite the distance, but remain connected – extended, "like gold to airy thinness beat".

In the meantime, the little cog is floating in weightlessness on the ISS.

A journey into space

Fitzpatrick embraced the ideas, and gave them form. The cog, she explained, represented a technology that pioneers once used to explore unknown territory. She experimented with the lightest possible materials, bamboo, paper, gold foil. Until the end, there remained the anxious question of whether the cog would survive the journey into space. At the end of February, a video proved it: The ship was floating safely in weightlessness on the ISS. "I would have loved a wreck," she said. The cog is not back on Earth yet, the curator Elizaveta Glukhova replied. Or, for that matter, on the moon.

Anyone who attentively strolled through the Max Delbrück Center on the Buch Campus and in Mitte during the Long Night of the Sciences encountered the interfaces between science and art everywhere. For example, in the "ART SCIENCE" exhibition on the Buch Campus: Not far from the watercolors by postdoc Maya Polovitskaya depicting scenes from everyday laboratory life, hung works of art produced by a computer with the aid of machine learning. They were created by computer scientist Deborah Schmidt of the "Image Data Analysis" platform. Most of her images show cells that do not actually exist. Only a few visitors were able to distinguish the fake cells from real insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas when they compared them. All images are renderings in which scientific data sets were converted into three-dimensional images. The beta cell even entered the scientific literature as the first 3D reconstruction of a microtubule network in mammalian cells.

How a computer visualizes data of individual cell types, for example of the brain, also inspired neurobiologist Bilge Ugursu to artistically despict results from single cell analysis. As an MDC PhD student, she is also conducting research on various mental disorders and approached them in sometimes somber abstract paintings

No servant of science

"The two spheres of science and art do not need each other, but they can stimulate one another," said Professor Anton Henssen. The pediatric oncologist from the Experimental and Clinical Research Center, a joint institution of MDC and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, studied for several semesters at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, the place where Joseph Beuys once taught. The researcher still paints. Sometimes Henssen mixes his centrifuged genetic material into his paints, sometimes it's the shapes of cancer DNA that spark his creativity. "It's two lenses pointed at the same object. Each offers a different perspective."

Under no circumstances should art be misunderstood as a servant of science, Dr. Katja Naie, Executive Director of the Ernst Schering Foundation, emphasized during a panel discussion on the Roof Terrace in Mitte. Equal footing, she said, is a prerequisite; there is no mutual dependence. "But the process is definitely similar," said Dr. Helena Kauppila, a mathematician and painter. "One commonality is certainly finding beauty in simplicity and precision."

And sometimes science can reveal biographical details of an artist that would otherwise remain a mystery. In the Beethoven House in Bonn, for example, locks of the great composer's hair are stored. "A souvenir from his deathbed, as was customary at the time," Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky told the audience in Café Scientifique at the BIMSB. Since the first reconstruction of a genome from hair in 2011, the scientist and pianist has been intrigued by the question of what information these curls might provide. Probably nothing about Ludwig van Beethoven's intelligence, nothing about his character, his musicality. Even on absolute hearing there are no meaningful studies, although it is inherited. But who was actually the "immortal beloved" known from a famous letter? Two women were in Carlsbad at the time of the separation, and both gave birth to a child nine months later. "Today, one could clarify this paternity without a doubt," Rajewsky said.

From Beethoven to the soundtrack of biomedicine

It would probably have been more important to Ludwig van Beethoven himself that posterity would understand his illnesses – and of course systems biology, Rajewsky's field of expertise, could contribute to this. However, Beethoven's suffering did not diminish his virtuosity. Anyone who listens to the compositions can testify to that. The audience in the large seminar room was no exception when Nikolaus Rajewsky sat down at the grand piano and played the A-flat Major Sonata op. 110. after his lecture. Beethoven was already deaf when he composed this piece.

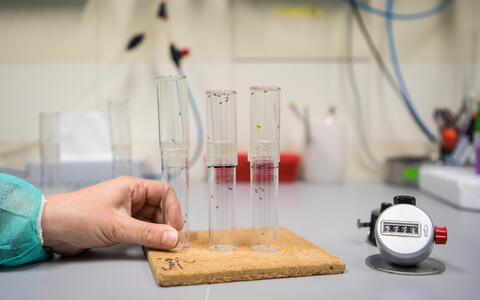

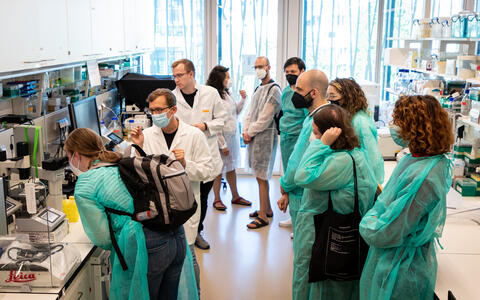

Long after sunset, the last expedition of the evening set out for the laboratories of fly researcher Professor Erich Wanker. Outside, jazz classics echoed across the campus in Buch; inside, visitors learned about the fruit fly as a popular research model during the late, fully booked tour. And while the lab Olympics paraphernalia were finally being packed away in the foyer in Mitte, beats could still be heard from the roof terrace. Not just any beats, of course. DJanes such as researcher Isabella Douzoglou from AG Birol had drawn inspiration from their everyday lives and set the tau protein to music, for example. Dancing to the soundtrack of biomedicine.

Text: Christina Anders and Jana Schlütter