The inventor of ultracool lenses

The high point of Dietrich’s career was the award of the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics for the design of the first electron microscope. Dietrich herself was not the recipient of the prize – that honor went to Berlin-based physicist Ernst Ruska – but she had spent many years of her life in the laboratory with Ruska and was part of his Berlin team. And thus the Nobel Prize was also a personal achievement for Dietrich, who was 67 years old at the time, and thus 13 years younger than Ruska.

A foundation for young women physicists

The fact that Dietrich’s impressive contribution to the development of increasingly powerful electron microscopes was overlooked by the Nobel Committee does not seem to have particularly bothered her. “She was an incredibly modest person,” recalls Dr. Svetlana Marian, who received a scholarship from her eponymous foundation in 1999–2000. “She was passionate about science, but she never pushed herself forward.”

Dietrich, who earned her doctorate in physics, created her own foundation – the Dr. Isolde-Dietrich-Stiftung – back in 1993. She wanted to use the money she had saved over the course of her life to support young women who aimed to pursue basic research in physics, in particular solid-state physics.

“She was a kind of second mother to me,” says Marian, who grew up in Moldova and now works in the development labs at Mercedes. “I used to spend whole afternoons with her, usually over coffee and cake, discussing countless topics relating to physical research but also other things that mattered to us personally.”

Mentally fit at an advanced age

Isolde Dietrich was born in Fürth on November 21, 1919, the second child of a linguistics professor and his wife. Her older sister also went on to study linguistics, but Isolde was drawn to physics instead. At that time, this was not an easy field of study for a woman to pursue. “She worked very hard,” says Marian. “She would be in the lab until late at night.”

Dietrich didn’t only work that hard to make her male colleagues take her seriously. “It was her passion,” says Marian. “Until her death on January 17, 2017 – which came very unexpectedly for me even though she was 97 – she would read science journals and attend lectures, and she was always keen to discuss with me the latest findings in solid-state physics.”

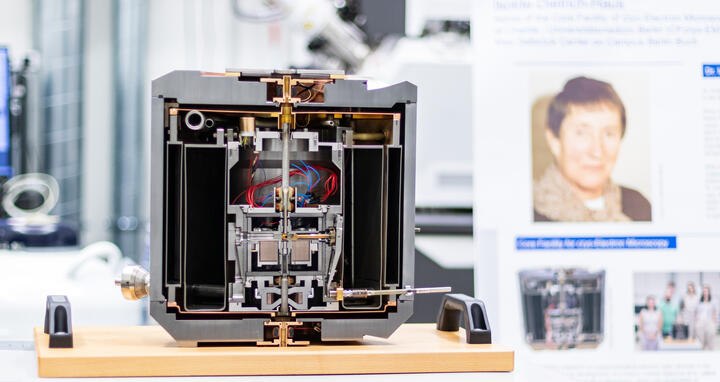

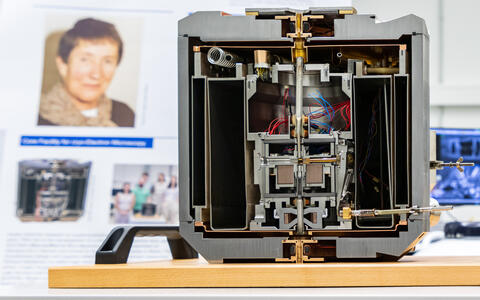

An invention by Isolde Dietrich: superconducting lenses.

Dietrich’s most important contribution to modern cryo-electron microscopy was probably her invention of superconducting lenses, a technology she pioneered during her time as head of a Siemens research lab in Munich in the 1960s and 70s. These lenses, which Dietrich also made available to Ernst Ruska, were cooled to temperatures close to absolute zero with the help of liquid helium. The advantage of such ultracold lenses is that electrons can pass through them very precisely so that they produce particularly sharp images of a sample.

A love for the great outdoors

When Dietrich wasn’t in the lab or reading her colleagues’ publications, she liked to be out in nature. She loved the mountains, which were easily reachable from Munich, where she lived until her death. She and her sister, with whom she was very close, were active in the Deutscher Alpenverein, Germany’s largest mountaineering club. In the summer the two sisters would hike, in the winter they would go skiing.

Isolde Dietrich with Svetlana Marian.

“They also travelled a lot overseas,” says Marian. “They went to Canada and Australia together.” Marian recalls the personal journals that Dietrich’s sister kept, and illustrated with photographs. “Sadly, those books are now lost.” She is therefore all the more delighted that a building on Campus Berlin-Buch will now be named after Isolde Dietrich. “She was always a big role model for me,” says Marian. “And I’m sure she would have considered it a great honor.”

Text: Anke Brodmerkel