Mutation puts women at higher risk of heart failure

Heart failure can be caused by a congenital heart muscle disease, or cardiomyopathy. There are a variety of causes, such as hereditary mutations in the PRDM16 gene, as Professor Sabine Klaassen and her colleagues demonstrated back in 2013. A team led by Klaassen and Dr. Jirko Kühnisch from the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint institution of Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, has now taken a closer look at this defect in mice.

The scientists discovered that mutations in the PRDM16 gene alter the metabolism of heart muscle cells, causing the heart to become much weaker. Female mice with this genetic defect experience significantly more heart problems than males, the scientists report in “Cardiovascular Research.” “This result is surprising because males tend to be affected by congenital heart failure earlier and more severely than females,” says Klaassen, who also works as a pediatric cardiologist specializing in cardiogenetics at the German Heart Center at Charité (DHZC).

Heart muscle no longer pumps properly

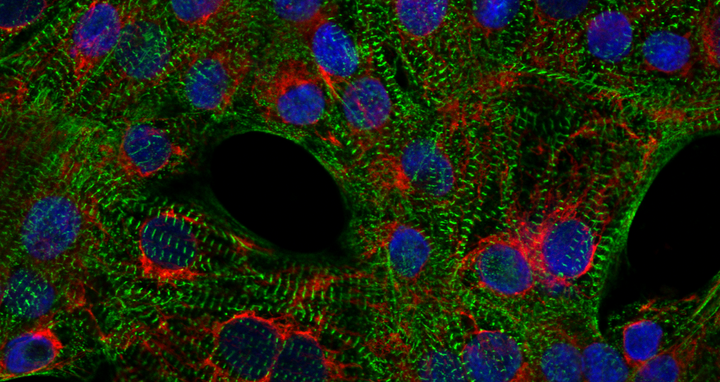

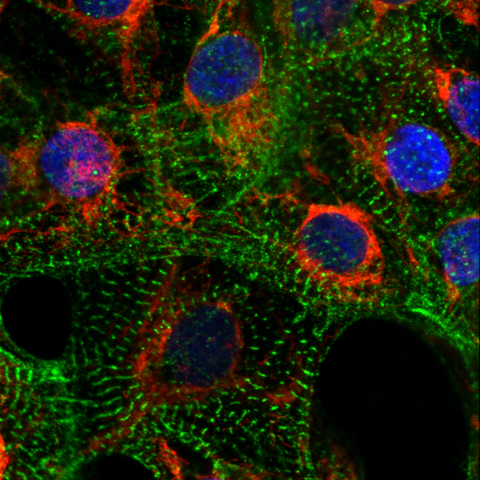

Cardiomyocytes with stained mitochondria (red), sarcomeres (green) and nuclei (blue).

In experiments with mice, which began in 2016 and were funded by the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH), the team has now been able to clearly confirm that mutations in the PRDM16 gene cause heart failure. The researchers also uncovered the underlying mechanism, showing that the deactivation of the PRDM16 gene alters the fat and glucose metabolism of the heart cells. This ultimately causes the heart muscle to become spongy, enlarged and unable to pump blood properly. “The gender differences may indicate that the metabolism of men's and women's hearts differs,” said first author Kühnisch.

The fact that the PRDM16 mutation may lead to metabolic heart failure is now stored in a genetic database that physicians can use for diagnostic purposes. “If a genetic test identifies this mutation, the cardiologist will know what causes the heart disease,” explains Klaassen. She adds: “We think that the genetic changes may also be relevant, albeit to a lesser extent, to heart failure that occurs in older patients.” Both scientists are affiliated with the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), which was instrumental in funding the studies.

Text: Janosch Deeg

- Press release: Novel gene for heart failure discovered

- PRDM16 – a therapeutic target for heart failure (German only)

Literature

Jirko Kühnisch et al. (2023): „Prdm16 mutation determines sex-specific cardiac metabolism and identifies two novel cardiac metabolic regulators“. Cardiovascular Research, DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvad154

Downloads

Cardiomyocytes with stained mitochondria (red), sarcomeres (green) and nuclei (blue). Photo: Klaassen Lab, Max Delbrück Center

Contacts

Prof. Dr. Sabine Klaassen

Head of the lab „Clinical and Cardiogenetics”

Experimental and Clinical Research Center

Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

+49 (0)30 9406-3319

klaassen@mdc-berlin.de

Jana Schlütter

Editor, Communications

Max Delbrück Center

+49-(0)30-9406-2121

jana.schluetter@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should be able to benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. This is why the Max Delbrück Center supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly-run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is 90 percent funded by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.