Zooming into flash-frozen cells

Our goal is to move from in vitro to in situ, that is, to observe processes directly in the cell.

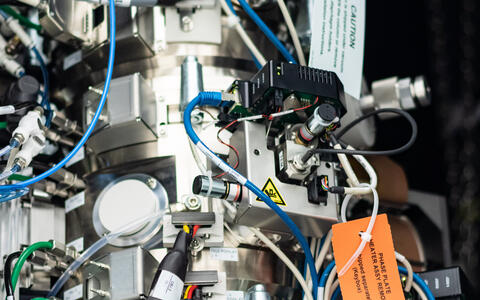

The new cryo-transmission electron microscope (cryo-TEM) on the Buch campus is four meters tall. The machine, which cost around five million euros, provides three-dimensional images of the tiniest structures within a cell. With the images at nanometer level, Berlin structural biologists render visible what happens when molecules within a cell collide.

“Our goal is to move from in vitro to in situ, that is, to observe processes directly in the cell,” Dr Christoph Diebolder said. He heads the Core Facility for Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) run by the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin together with the Max Delbrück Center and the Leibnitz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP).

On September 15, 2023, the Core Facility was ceremonially opened with a scientific symposium. On the same occasion, the highly customized research building that the Max Delbrück Center built for cryo-TEM was named: Isolde Dietrich House. The physicist, who died in 2017, worked for a long time in Berlin, paved the way for electron microscopy in the laboratory of Nobel Prize winner Ernst Ruska. “I’m sure she would have considered it a great honor,” said Dr Svetlana Marian, who knew Dr. Isolde Dietrich well and attended the opening. “She was an incredibly humble person.”

“Together, we have achieved something here that no institution can afford on its own. Such an infrastructure attracts excellent scientists to Berlin,” said Professor Christian Hagemeier, Vice Dean for Research with a Preclinical Focus at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The facility's large-scale equipment on its own costs around eight million euros. Charité, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Freie Universität have raised funds for this from the German Research Foundation and the state of Berlin.

Professor Holger Gerhardt, Dr. Christoph Diebolder, Dr. Svetlana Marian, Professor Christian Hagemeier and Professor Christian Spahn in front of the Isolde Dietrich House.

More than one high-end instrument

A cell one micrometer in diameter would be too thick to image using cryo-TEM; 300 nanometers are the maximum. To be able to prepare such delicate specimens, the researchers at the facility have another top-class instrument at their disposal: a dual-beam FIB SEM, which is a cryo-scanning electron microscope with a focused ion beam. An electron-permeable lamella is milled out of the flash-frozen sample, such as a human cell, with the ion beam. To get precisely the section to be viewed in the cryo-TEM, the corresponding molecules are marked beforehand using a cryo-CLEM, a correlative light electron microscope. The lamella, this very tiny sample, then goes into the cryo-TEM.

The cryo-TEM stands like a huge vault in a high-ceilinged white room, where a ventilation system emits a constant hiss. This is a necessary feature, as the device is just as sensitive as it is large, and unable to tolerate temperature fluctuations or excessive humidity. The room’s humidity is therefore kept under 20 percent, which means visitors get thirsty very quickly. Vibrations and electromagnetic fields are also problematic. A concrete foundation 1.25 meters thick has therefore been placed underneath the building to cancel out underground vibrations. And with its double walls, the building is also a sort of house within a house. The research building with about 156 square meters of floor space cost about 2.9 million euros.

The Isolde Dietrich House seen from the outside; next door, the Max Delbrück Center is building the Imaging Innovation Center.

Next door, the Max Delbrück Center has already started work on the next construction site. “This is where our Imaging Innovation Center is being built," said Professor Holger Gerhardt, Vice Scientific Director of the Max Delbrück Center. "Physicists, biophysicists, life scientists and bioinformaticians will advance the latest microscopy techniques and image analysis methods in this building. This is an optimal match for the Isolde Dietrich House.”

Further information

- Isolde Dietrich: The inventor of ultracool lenses

- The opening symposium

- Core Facility for Cryo-Electron Microscopy

- Construction begins on new Imaging Innovation Center

Photos to download

- Professor Holger Gerhardt, Dr. Christoph Diebolder, Dr. Svetlana Marian, Professor Christian Hagemeier and Professor Christian Spahn in front of the Isolde Dietrich House.

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center - The sample needs to be flash-frozen.

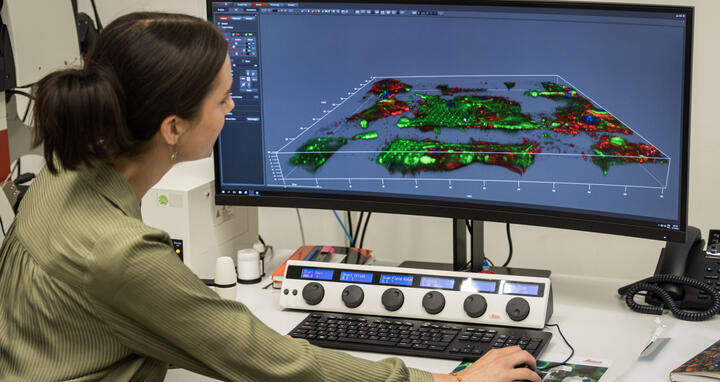

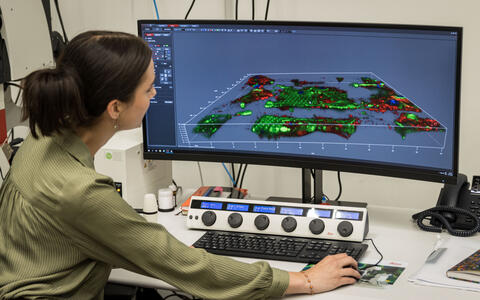

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center - Greta Päffgen marks the precise section to be viewed in the cryo-TEM using a cryo-CLEM, a correlative light electron microscope.

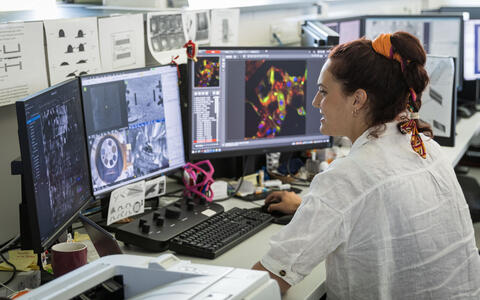

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center - Metaxia Stavroulaki mills a fine lamella out of the sample, using Dual Beam FIB SEM.

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center - Dr. Thiemo Sprink explains how cryo-TEM works.

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center - The cryo-TEM is a delicate instrument.

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center - The Isolde Dietrich House seen from the outside; next door, the Max Delbrück Center is building the Imaging Innovation Center.

Photo: Felix Petermann, Max Delbrück Center

Contact

Jana Schlütter

Editor, Communications

Max Delbrück Center

+49 (0) 30 9406 2121

jana.schluetter@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center

-

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The Max Delbrück Center therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.